A New Mission Statement and The Apostolate of the Methodists

By Taylor Burton-Edwards

A New Mission Statement

On May 19, 2016, the General Conference of The United Methodist Church revised the second statement of the paragraph that includes our mission statement. That second sentence now reads: "Local churches and extension ministries provide the most significant arenas through which disciple making occurs."

Followers of my former blog emergingumc or persons who have followed my presentations about the network ecclesiology of early Methodism over the years will know that I see the primary charism of Wesley's Methodism not consisting of congregations alone, but of congregations (local churches) in network with discipling groups. The Wesleys per se founded zero congregations. They started religious societies with a laser focus on helping persons who were ALSO actively participating in congregations (Anglican for the most part, but not exclusively) to experience the assurance of justifying grace and grow in sanctifying grace toward "entire holiness of heart and life" which they also described as "perfection in love in this life."

Understood this way, what early Methodism was actually creating, and what the Wesleys were leading, was a form of extension ministry.

I praise God that our mission statement now reflects our historical reality, as well as the larger historical reality, that since the early 6th century at least it has been religious societies (monasteries and other groups) through which the most "hands on" and accountable processes of discipling have occurred, and most often alongside than integral to the work of congregations.

The Apostolate of the Methodists

So what does all of this have to do with our apostolate as Methodists?

It goes back to recognizing that both congregations as we have them and discipling groups as we have them (and as early Methodist societies, class meetings and bands fundamentally were) derive from the same stream of apostolic ministry started by Jesus and handed down to his original apostles, and from them to the rest of the church.

The congregational format of Christianity and the support networks and leaders that have been primarily related to it (dioceses or synods and their bishops, and, later, presbyteries and conferences and their leaders) have a fairly defined and traceable lineage from generation to generation. One can speak at least in broad terms of there being a kind of historic succession of leadership for the congregational format of Christian faith that stretches back to the time of the apostles.

We have far less documentation about how the leadership of discipling groups in all the varieties in which they have emerged over time has passed down. Rather, it seems the Spirit has raised up many people across the generations, many of the laity, who have carried on this significant part of the original apostolic work in varying ways at varying times. The peculiar work of the Spirit led by the Wesleys and labelled Methodism first by its detractors is among these, and it continues in a variety of different forms, to this day.

Discipling, or in the Wesleys' terms, helping persons come to the experience of assurance of justifying grace and then grow in sanctifying grace toward perfection in love in this life, is the heart of our apostolate as Methodists.

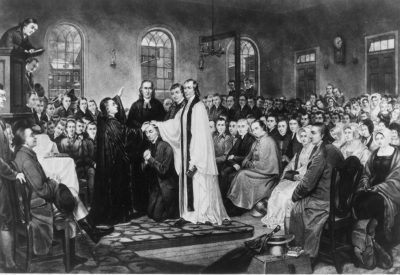

United Methodists have at best an irregular claim to stand in historic succession as it is usually described, and it is good for us to admit that. The historic succession is typically connected to the congregational format of Christian faith, and specifically to a line of ordinations of and by bishops. John Wesley was not a bishop, yet he ordained not only elders but also one (as Superintendent) who would later take on the title and essential role of bishop (Thomas Coke, who then ordained Francis Asbury, as depicted in the image above). It is primarily through Asbury, himself thus irregularly ordained, that the vast majority of our ordinations come.

This does not mean our ordinations are in any way deficient. It means they may come through a different but equally legitimate stream of apostolic work than those of the historic succession.

I'd like to suggest it also means something else. The fullness of the apostolic work and thus of the continuing apostolate, stretching back to Jesus and his first apostles, is not fully contained in either the historic succession or in the discipling/society work which has been our particular charism. The fullness of the continuing apostolate is found as the emergent property of the interaction and collaboration of both.

This suggestion would have some influence on how we may conceive of rites of full communion and in particular the rites of mutual recognition or reconciliation of ministries with churches who have a claim to historic succession in ways we may not.

Part of what it says is we as United Methodists have both something to give and something to receive in such rites and processes. We bring an apostolate of intentional discipling, and both a heritage and an ongoing practice of such ministries, even if in a diminished sense relative to our founding. Those who have a better claim to historic succession than we do bring to full communion more of the gifts of that stream of the original apostolate. When we each offer these gifts of the apostolic deposit to each other, and each take up these gifts with all earnestness, we cannot but all be blessed in the mutual exchange.

Image Credit: The Ordination of Bishop Asbury. Public Domain.