What Is the Great Commission? Part I: Text, Translations, and Culture

By Taylor Burton-Edwards

Companions,

Companions,

We probably all think we know the answer to the question.

But do we?

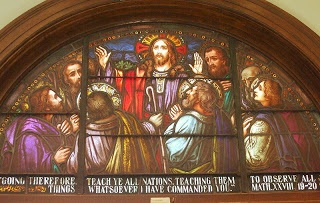

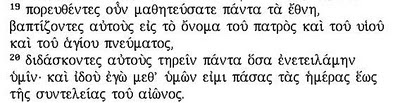

Here are three Protestant translations of the text-- Matthew 28:19-20-- King James (the standard English translation prior to the middle of the 20th century), Revised Standard (the mid to late 20th century "standard" or "mainline" translation in the KJV tradition) and Today's New International Version (2005, but heading for the dustbin because it was deemed "too radical" in some of its translation choices by some of its primary "market" of North American Evangelicals). The image above contains a fourth-- from the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Saint Patrick in El Paso, Texas. And for good measure, I've included an image of the Greek text below, with gratitude to Anthony Fisher's Greek New Testament project.

19 Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost: 20 Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and, lo , I am with you alway, even unto the end of the world. Amen. (KJV)

19 Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, 20 teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age." (RSV)

19 So wherever you go, make disciples of all nations: Baptize them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. 20 Teach them to do everything I have commanded you. "And remember that I am always with you until the end of time."(TNIV)

Read the translations, and the Greek if you can, and see what observations you might make.

Here are a few of mine.

Some Observations about the Greek Text:

1) The Greek text itself has only one main verb in verse 19-- matheteusate. All the rest are participles. That includes the opening word, poreuthentes-- which might be best rendered something like "As you've journeyed." The TNIV and the Roman Catholic translations got this right. The KJV, RSV, NIV, and the upcoming Common English Bible translate it as an imperative, "Go."

2) The main verb of verse 19-- matheteusate-- is an entirely different verb than the opening participle of verse 20-- didaskontes. Both have some reference to teaching, but in very different ways. Matheteusate comes from a verb which we have no "normal" English equivalent for. We tend to render it "make disciples" as RSV and TNIV do (and NRSV does as well), but even that is a bit misleading in our post-industrial culture. The construction "make X" for us just automatically implies production-- doing something like making widgets. Our brains just go to that interpretation without us ever having to think about it. It's that imbedded. With such an immediate, unconscious but incredibly powerful response to this construction, we then approach "making disciples" as a programmatic issue handled by systems, assembly lines or black boxes. In our day, given our collection of "normal" ecclesial systems, particularly in The United Methodist Church, we see it as the desired end product of a congregation.

Our own cultural frame here over-determines and distorts the translation and the interpretation.

A quick note about culture and translation. Of course, one's current cultural frames at least somewhat determine both the translation and to some degree the interpretation. If that doesn't happen, the meaning is entirely opaque to the readers today (or in any day or culture for which a translation is intended!). But at the same time, there has to be every effort at trying to capture what the original hearers, writers and readers of a text from another culture were trying to communicate in their particular cultural context. The work of translation needs to be about privileging that "original" set of meanings within the frameworks of the culture for which it is made as much as possible. It's a tricky balancing act, and always hard to do, and impossible to get precisely right-- all the more the greater remove one is from the original culture or reliable knowledge of that culture.

The problem I'm suggesting here then is precisely that of balance. I'm suggesting that those who choose to translate this "make disciples"-- precisely because of our culture's automatic equation of "making X" with a mechanical process or some kind of product, AND because that connotation is entirely absent from the original culture that used this term-- have, perhaps unwittingly, left wide open our culture's usual readings to over-determine the text in ways easily misinterpreted as production.

And that's unfortunate, because there is no "production model" implied at all in this verb.

None!

If there were any interest in conveying the notion of producing or making anything, the Greek construction would have been "poiein mathetes"-- "to make disciples." THAT would mean production. But the idea that one could produce people like one produced a pot or even a poem (poem comes from the same root as the verb, to make) would have been beyond bizarre to the mind of any of these cultures, and so also to Jesus. So it's no wonder the Greek uses the verb, and not a verb plus object construction here.

The "thought world" behind the verb and the actual practices that embodied it were instead deeply relational. It's about "discipling people"-- initiating and engaging discipling relationships with people, just like Jesus did with his own disciples. It's about the hands-on, 24/7 watchcare of a shepherd for sheep (to use another biblical metaphor, though not quite as rich as that of discipleship). It's about investing deeply in the lives of others "laying down one's life for friends"-- and yes, that is the primary meaning of that phrase in Greek, too, by the way!-- so that they begin to live as you do, so that you pass on what you have received from those who discipled you just as Jesus passed on what he received from the Father. It's through that process that people move from being servants of the master to being friends of the master-- not "by nature," and not by fiat, either our own or that of the master.

We just don't have "to disciple" as a verb-- at least not as easily understandable as "teach" or "preach"-- in part because we no longer have as many instances of actual "discipling" going on. Where we do, it's considered exceptional, or a luxury, or something done by "fanatics," or something we do, sort of, to prepare people for ordained ministry. It's certainly not viewed as an expectation or even a realistic hope for "ordinary Christians."

3) The participle for "teaching"-- didaskontes-- does mean "teaching" in more of an "ordinary" sense, but even here the content being taught-- "to keep everything I have instilled in you"-- relates again far more to hands on discipleship (matheteuein) that to transmission of "facts" or formal doctrine per se. Where do we have teaching that actually does that? (Ritual can do this-- if indeed we keep it and don't keep playing with it so it can actually transmit nothing because everything changes too much. General Rules can do this-- if we keep them for conscience sake rather than mend them for our own convenience).

4) The promise to be with us in verse 20, across the four centuries of translations represented above, presumes a fundamentally historical timeline with a beginning, a middle (now) and an end. The Greek text itself points to a fundamentally apocalyptic timeline that is simultaneously being unveiled every day here and now and that also has a linear aspect, but in a very different way. A more literal translation might be, "I am with you all the days [historical timeline] up to and including the complete fulfillment of the age [apocalyptic timeline]."

So the existing translations underwrite a version of history that keeps delaying the possibility for parousia ("presence alongside" or "arrival" literally!) while the Greek says parousia is happening at any time fulfillment is happening rather than only after some predetermined number of historical years or the collapse of life or civilization or some such (implied in language of "end"). Augustine's meditations on time in the Confessions were still taking that sort of apocalyptic timeline seriously in the West. Augustine was clear that the only time we have is the present, and both the future and the past are present in the present. Few others in the "mainstream" Western tradition followed in that path-- the visible trail almost completely ends there, or goes underground, as it were, resurfacing in a variety of millennialist and spiritualist movements (often at the center or the fringes of heretical movements) ever since.

Some Observations about the Translations

First, an overarching observation. All of these translations seem at least to reflect (and probably also to promote) the epistemological, ecclesiological and missional assumptions of their translators or those for whom the translations were made.

As I've noted above-- one would and should expect that.

As I've also noted above in at least one instance, what this means is that every translation-- including the observations about translation I've offered-- have to be considered carefully and critically to "suss out" to what degree those overarching or underlying assumptions of the translators or readers of their day may be overdetermining and therefore distorting the meaning of the text.

So here are some observations about how each of the translations on offer may have been doing just that. Feel free to add your own-- or disagree with these!

King James Version (1611, with minor alterations of spelling and wording along the way)

"Go ye therefore and teach all nations... teaching them to observe all things... even unto the end of the world"--

There would have been no virtually no "discipling" functions anywhere in 1611 in the Church of England. The monasteries were closed, their lands given to the crown. The monks were either banished or in hiding. Preparation for ordained ministry might still have carried this function, but that may have been about the extent, at least, of any non-underground activity in this direction. So, if only because of that, it's little wonder that "teach" was chosen for both terms.

It's also possible that the distinction in the Greek between the meanings of these two verbs (matheteuein and didaskein) was unknown to the translators in this period.

In its day, most readers and teachers of this text would have applied its meaning primarily to the apostles then and their representatives "now"-- the bishops directly and proximately the priests. This also fits with the Reformed view of the "pastor" as "chief teacher"-- and teacher on an academic model. That's also why you see clerical garments looking like academic ones out of this larger Reformed tradition that was deeply influential on the English church in that period and to this day.

"Teaching them to observe all things" in this culture would have been about getting people to conform to the basic customs and laws of the church and the realm-- remember, this is a state church!

"Even unto the end of the world" underwrites the then current Western secular linear view of history.

Now-- there's one more important word here, though less important in 1611 than it would become not much later: "Go."

The translators had to know that the verb before them was a participle and not an imperative. The Vulgate had it as a participle (euntes). Every Greek text had it as a participle. Yet they chose imperative-- or at least what later generations would clearly read as imperative.

Here-- a side note about the English of the day. "Go ye" could actually have been understood either as an imperative ("get ye going") or as a participle ("as ye go"). So it's not entirely that they were wrong, but rather, perhaps, that they went for vague rather than clear.

Unfortunately, by the 18th century, if not earlier, the latitude in meaning of such constructions appears to have generally collapsed, so it could only be understood as an imperative.

This one word choice then came to underwrite much of the fervor behind the religious rationale for the British Empire and the English-speaking missionary movement through the 19th century and well into the 20th. Combined with "teach all nations" it supported the notion that the means of the missionary work was to take "the stuff we know" (because we know the right stuff) to "all the nations" and seek to make them know it, too, verbatim, just like the English (or the Americans!) did, because "the stuff they know" is totally wrong and we've got to teach them otherwise. Jesus said so. It's a command. Go! Teach! Can someone say "Colonialism?"

The one major missionary movement that didn't follow this model of "everything about us is right, and everything about you is wrong, and we can't possibly mix them or presume you have anything to offer" was that of the Jesuits. They were doing what we'd now call "indigenous mission" back in the 16th and 17th centuries in India, China and South America-- and getting into real trouble for doing so!

So who was this commission for? The Church hierarchy who take care of this "for us," and later, also for missionaries and the organizations that sent them.

Revised Standard Version (1946)

"Go therefore and make disciples of all nations... lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age"

Though it placed itself intentionally within the King James translation family, the RSV was pre-eminently the work of biblical scholars who were trying to get the findings of their scholarship since the 19th century reflected in the translations used in the churches themselves.

That work shows up in two places in this translation.

First, the scholarship in ancient Greek was such at this point that it was very clear that one could no longer equate "matheteuin" and "didaskein" in the translation itself.

Second, there had also been enough work on apocalyptic literature and apocalpytic world view in the academy-- even if such perspectives were viewed as "pre-modern" and "mythological" in mainstream scholarship-- that translating "aionos" as "world" was a non-starter.

But "Go" remained.

This was "The Christian Century," after all, with the missionary movement, now led largely (though not entirely) by the US still very much on the "offensive" (especially after World War II) to "reach all nations" (nations understood at this point as political entities-- the term would have referred to people groups in the first century) with the gospel. So in the "mainstream" communities that were using the RSV, this text was seen as a lively prod to the ongoing missions movements and used primarily by the "established" denominations and their "foreign missions" agencies both to sustain financial support for their operations and to recruit persons to work "in the mission field."

A major case in point-- the hymn "O Zion Haste"-- appeared in no less than 360 different hymnals of all sorts from its first publication in 1894 through 1979, and still appears in 12 hymnals (including the UMH, # 573) since that time. Its last verse-- the "payoff line" if you will-- is "Give of thine own to bear the message glorious; give of thy wealth to speed them on their way; pour out thy soul for them in prayer victorious; O Zion haste, to bring a brighter day." (Source for statistics: The Hymnary).

So make disciples of all nations" was often read in a way that presumed that America was already essentially Christian-- and more particularly that its WASP establishment at every level (with the possible initial exception of the Germans and "communist sympathizers" early on) certainly was. Most of the content and manner of teaching the gospel at this point was still "colonialist" in its assumptions, even though the British Empire and all the other European empires that had extended their reach-- and their versions of Christianity-- into the Global South and East-- were tottering on the verge of collapse.

Lesslie Newbigin was a voice in the Protestant missions wilderness advocating indigenous mission-- but it was a very big wilderness at the time! That he was heard at all was probably more because of his work and the relationships he was able to forge with recognized leaders on ecumenism, which would have been respected by the "establishment. " If he had not had those powerful friends, the established missionary interests might otherwise have found his missionary ideas deeply threatening to the still deeply colonialist mission enterprises they also represented and tried to keep funded.

Today's New International Version (2005)

So wherever you go, make disciples of all nations... I am always with you until the end of time.

The TNIV was billed as a revision of the NIV with better attention to the biblical texts-- a more literal reading and less of a dynamic equivalence reading, which had informed the NIV-- for today's Evangelical Christians in the English speaking world.

I think you can see that audience clearly in view in this translation.

First, we're back to something approximating the King James at close of verse 20-- "the end of time." "The end of the age" may have been too associated with "liberal" usage to pass muster. So the apocalyptic timeline proposed in the Greek is again buried, and a secular chronological one put in its place.

Second, it makes no distinction between y'all and you (singular). It's y'all in Greek. For an individualistic audience (which American Evangelicalism tends to be) the default reading would be singular. Wherever you go, as an individual, make disciples. Always be about the business of producing disciples-- yourself.

That kind of message almost sings in a variety of strains of the larger evangelical missional and emerging church movements.

It doesn't play as well, though, for those entities that have significant investments in "missionary companies"-- whether "old school" (colonialist) or "new school "(indigenous). If this commission is now transferred to every single Christian, as an individual, it's much harder to make the case that my first and most financially costly response will be to support a denominational or other missionary organization with my money and effort. Maybe on the side-- but not as job one.

It also sings with the sense of the original Greek about making disciples of all nations-- at least a little better. "Nations" is still problematic, frankly-- still too politically defined in any US default reading. "Goyim" would have been better! (Well, at least in the Jewish neighborhood where I grew up!). Maybe it's there as a reflection that a lot of evangelical assumptions, even within the missional movements, are still Constantinian at this point.

But if it's up to me to be making disciples of all nations wherever I go, and I really only go in the US for the most part, then we do have something a little closer to the Greek. This translation recognizes the nations are those right around me. It recognizes that the US is a nation of many ethné-- many people groups. And it recognizes that Christianity is thus fundamentally multi-cultural from the beginning. WASP won't cut it anymore. Even the homogeneous unit principle made popular by the church growth movements of the 1970s and 1980s is now a non-starter. That's real progress!

But we're still left with "make disciples"-- language that we're still pretty hardwired to interpret as some sort of a production demand. And we're still left with this at a default individualistic level. It's my job as an individual to go make more of these "disciple-widgets" out of people, whatever those may be.

Maybe my congregation gives me some tools I might be able to use to do this. Maybe it doesn't.

Or maybe the idea is that it's really my job to get more people into things my congregation is doing-- get them into the black box of the congregation-- and then they'll become disciples, like I did.

How you read this might depend deeply on how the interpretive communities with which you mostly interact make sense of it with you-- or perhaps more likely, for you.

So What Is the Great Commission-- Today, Now, Where You Are?

I'll leave that for you to answer and discuss on this blog or elsewhere.

For another look at how this plays out in evangelism more broadly, see Frank Viola's blog article, Rethinking Evangelism.

And in Part 2 of this mini-series, I'll look at and invite your conversation about what some of the insights here might mean relative to the mission statement of The United Methodist Church.