Worship and Discipleship, Part 5: Fix, Practice and "Earlier" English and American Methodism...

By Taylor Burton-Edwards

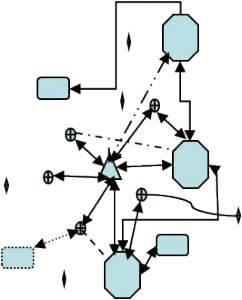

Colleagues, Leave it to a liturgy geek-- or maybe just a geek-- to come up with a weird, unlabeled diagram with far too many connections and implications to explain in a single blog post. Well, given that this diagram has actually appeared in this form several times on single slides (or pages) of some larger presentations and scholarly papers I've done on the emerging missional way and early Methodist network ecclesiology, maybe this is an improvement. No, I don't make any promise that this diagram will make perfect sense to you or to anyone by the end of this post. But I do hope it may make a bit more sense then than it may here at the beginning. Just humor me a bit, eh?

Leave it to a liturgy geek-- or maybe just a geek-- to come up with a weird, unlabeled diagram with far too many connections and implications to explain in a single blog post. Well, given that this diagram has actually appeared in this form several times on single slides (or pages) of some larger presentations and scholarly papers I've done on the emerging missional way and early Methodist network ecclesiology, maybe this is an improvement. No, I don't make any promise that this diagram will make perfect sense to you or to anyone by the end of this post. But I do hope it may make a bit more sense then than it may here at the beginning. Just humor me a bit, eh?

In the meantime, let me review some of the ground we covered in part 4. We noted that Finney and the revivalists had made the assertion that revivals, and in particular "The Fix" (a strong emotional and physical response to anxiety understood to be generated in and by the Holy Spirit in the context of the revival meeting itself through the "right use of measures") both were necessary to produce real conversion and real holiness in his own day because what the congregations were doing did not and likely could not produce these effects, and, further, that this had always been so throughout the history of Christianity. We noted that this charge of the disinterest, impotence or incompetence of the congregations on these matters was very likely accurate in the large, if not entirely fair, given that, in fact, congregations were neither designed nor trying in their ministries to produce such effects in most of their members for the most part, and hadn't been for centuries! But we also noted that the second claim, that "The Fix" was always the means by which God had always generated new Christians and holy living was actually a serious misreading at least of early Christianity, one that completely ignored the intense efforts at practical formation involved in the catechumenate.

We noted there, as well, that the catechumenate, as a process, had in fact been reasonably successful and generating congregations full of real Christians who were really growing, at least as long as the intensity, purposes and processes that underlay it and surrounded it were in place. Indeed, as a number of historians have shown, by far the greatest rate of sustained expansion of the Christian faith so far occurred between about 110 (perhaps 25,000 Christians total) and 310 (estimates vary from 2 to 6 million Christians), before the legalization of Christianity in 315, an 80 to 240 fold increase in two hundred years. This rate of increase cannot be accounted for by births alone, and there is no evidence that these occurred through any "mass conversions" in this period. Instead, the vast majority of these were new converts to the faith, invited to this way of life by other Christians, and then given some intensive form of the catechumenate (its details varied from place to place, but the normal time period seems to have been established around three years by the beginning of the third century) prior to being baptized, which also meant, in many places, prior to ever seeing at all, and in others, ever participating in the entirety of "regular" Sunday worship (Holy Communion). If they were there at all, the "catechumens" were dismissed after the "service of the word" and typically before the prayers of the people while the baptized faithful remained.

By contrast, let me suggest that there is no evidence that "The Fix" has ever generated congregations full of real Christians, either before or after 375. It may certainly have "added to the number" of people within congregations who actually became and grew as committed disciples of Jesus. But it did not fundamentally alter the character or the composition of those congregations themselves, with the possible exception of those who, deeply involved in revivalism itself, split off to form their own congregations with a decidedly more sectarian and almost perpetually revivalist flavor. Even Finney wanted none of that!

To sum up all of this for the 19th century revivalist context, the realities were these. Congregations practiced and taught their members to practice "congregational" things-- public worship of God, basic Christian theology (in their particular flavor), some means of caring for each other, and being a respected institutional player in the local community (all of which were good things, but none of which created or supported the expectation that most members would live as fully committed disciples of Jesus). Revivalists, meanwhile, such as Finney, used "The Fix" in revivals in order to "stir up" the passions of people inside and outside the existing congregations to create "real Christians," i.e., those who would constantly and actively strive the follow the way of Jesus in personal life and social influence.

So in the congregations there were practices of worship being taught-- though with few exceptions, these were becoming both theologically and ritually thinner over time-- and some practices of interpretation of scripture to fit the particular confessional/denominational bent. And there was the "new measure" of the revival and "The Fix" to move some of these into more fervent action.

But almost no one, anywhere on this scene, had either a means or a method actually to train the majority of their people intensively in the practices of Christian discipleship.

Almost no one-- but the Methodists!

Early Methodism as a Restored Catechumenate

The invitation into early Methodism was a wide open one. All it took to start the path toward becoming a Methodist-- that is a full member of one of the early Methodist societies-- was a "desire to flee the wrath to come and to be saved from sins." That desire alone with the sufficient ticket to enroll you in a "trial class meeting," a small group of 7-12 people meeting weekly, often on Thursday evenings, led by a trained leader where, for a period of at least six months, you were being taught and held accountable to live the practices commended by "The General Rules" by, in these meetings, learning and using the practices of prayer, searching the scriptures, receiving practical and scriptural teaching, and engaging in "holy conversation" about one's progress in living them out.

Simply being in this "trial class" did not make you a Methodist, however. Not until you had been part of this group for six months and your class leader asked for you to be admitted to the society, upon his or her recommendation, and then not until the society had examined whether you had actually made sufficient progress in living out the practices of the Rules that you were likely to continue to do so, were you in fact admitted as a full member of the Methodist Society, and therefore (assuming you remained in good standing) eligible to participate in more of its life-- particularly its more "private" rituals such as the Love Feast and the Watch Nights or Covenant Ceremonies. And only then, and only by remaining in good standing by continuing to progress in living out these practices-- all of them-- could you expect to be brought into leadership in the Society or, later, the Conference.

Some compared the rigor of this meddlesome process that messed with how people lived their lives and both required and showed them how to live differently to the novitiate of the monasteries and religious orders, and so called the Wesleys and the Methodists "papists" (i.e., in league with the Pope, hardly a compliment in 18th century England!). Others called them "Pelagians" (followers of the teaching of the ancient British bishop, Pelagius, declared a heretic by Augustine and a few others for seeming to promote the idea that people could be saved more or less by their works) for focusing so much on practices-- practical ones, devotional ones, personal ones, social ones and the fullness of the ritual practices of the existing congregations (mostly, but not entirely Anglican) of his own day. The Wesleys answered such objections often and firmly, and frequently by referring to what they were doing, actually, as "experimental Christianity."

By that term "experimental" they did not mean anything like "trying something out to see if it works." Rather, they meant something closer to, though not quite the equivalent of, our word "experiential." That is, what they were up to, and helping a growing number of Methodists across England and North America to do, was concretely helping people live out the fullness of Christian discipleship, really and practically, in their own lives then and there. In short, they were enrolling people in a catechumenate-- not to learn a catechesis (a list of right answers to doctrinal questions) but to learn to follow Jesus. The General Rules were nothing more and nothing less than a set of practices by which persons could put living human flesh upon and experience the Spirit's breath through the ritual "bones" of their baptismal vows. Teach people how to live these practices, and both support and hold them accountable for continuing to do so, and they will be more likely to follow the way of Christ and participating fully in the ministry of the whole church, ever growing in holiness of heart and life.

One never graduated from a class meeting, though one would graduate from the "trial class meeting" into a meeting of largely full members of the Society. Membership and participation in class meetings was, and remained, a necessary precondition for ongoing membership in the Methodist societies in England. It would also remain, at least in the Books of Discipline, a continuing precondition for both initial and ongoing membership in what became the "societies-becoming-congregations" of The Methodist Episcopal Church through the early decades of the 19th century.

The greatest expansion of Methodism and Methodist influence in North America happened not with the "church a day campaign" of the later 19th and early 20th centuries, but rather with the multiplication of these "little cells of practiced believers" who were starting colleges, working against slavery, building hospitals, educating children, caring for the elderly and the poor, organizing labor unions, and preaching the gospel in deed and word in the late 18th and early 19th century.

These "little cells of practiced believers" were the heart, but not the whole, of the early "Methodizing" of America. The "whole" was church-- these cells, plus the societies-becoming-congregations (with the opportunities and challenges that hybrid brought!), plus all the other ministries and institutions these "practiced believers" were starting-- the network or "connexion" of all of them (see- that diagram up there does mean something!) and not any one of them alone. The fullness of the expression of church could emerge out of all of these different kinds of expressions of Christian community and ministry, each doing its own particular work well-- church as network, not simply as congregation or small group or ... revival meeting.

Now, none of this is to say elements of "The Fix"-- powerful emotional and physical responses engendered in group worship practices-- were absent from Methodist life, or not important in it. Not at all. If we are to believe the many chronicles of early Methodist leaders on both sides of the pond about what they saw occurring in society meetings, field preaching, and even the later "quarterly meetings" such times of intense emotional encounter and expression in worship were not only not uncommon, but received as signs of the Spirit's work in their midst to help promote new faithfulness.

But the deal here is, these earliest Methodist Episcopalians (after 1784) did not rely on "The Fix" alone. "The Fix" could happen or it might not. Come what may, they were still training people to live the General Rules in weekly class meetings, worshiping weekly as well in Society or later congregational worship ( a hybrid of society and Church of England practices), and celebrating Holy Communion as often as there was an elder present who could preside -- and the latter using a ritual only slightly altered from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

Why that kind of Sunday morning worship, and why that kind of "rote" sacramental practice? As the Wesley's both argued in their oft-republished tract, "Reasons against a Separation from the Church of England," it was because

"The Prayers of the Church (i.e. the Church of England, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer)... are substantial Food for any who are alive to GOD. The LORD'S Supper is pure and wholesome for all who receive it with upright Hearts.... The more we attend it, the more we love it, as constant Experience shews. On the contrary, the longer we abstain from it, the less Desire we have to attend it at all."

So what did these early Methodists have? "Schools" for teaching the practices of the Christian life (class meetings), worship primarily as a practice or a series of practices (Sunday morning), and worship opportunities where "The Fix" could also occur (both class meetings and Sunday evening society meetings/worship). All of that. At least initially.

But not for long...

So... back to the period of the revivals, beginning in the late 1820s. At least in theory, if you did "come to the Lord" at an early 19th century revival, the Methodists who were part of that revival would not immediately enroll you as a full member in the church. They would instead immediately enroll you in a trial class meeting where you would learn the practices of the Christian life, the General Rules, and how to live them. They would invite you to Sunday morning worship, but you would not be admitted to communion or to love feasts until you were a full member with a ticket in hand to certify you were a member of the society (or later, congregation) in good standing. And then, again at least as the Discipline had it, if you made good progress, you might be considered for admission to the church as a member, and sustained in such membership, but only provided that you continued to live out the General Rules in ways verified by the leader of the class every quarter in which you continued to be enrolled and participate.

Except that, of course, what the Discipline stated was supposed to happen wasn't exactly what was really going on. Already by the 1830s, coinciding with the height of the revivals, there are signs that participation in the class meetings as a necessary precondition and ongoing condition of membership in the Methodist Episcopal Churches was beginning to fall by the wayside. There was still "exciting preaching" (as Finney documents!) but in essence "The Fix" and some sense of doctrinal orthodoxy were already starting to replace initial and ongoing participation in the classes as the "sine qua non" that actually got you into or kept you in membership. The six month waiting period still applied, and probably almost universally (that could be fairly easily checked and confirmed in church minutes, after all). But the actual training-- the practices? These were steadily falling away. At least among the "dominant culture"Methodists. (The story here is very different for AME and AME Zion!).

This became even clearer in the Disciplines of the 1840s, of which we have originals here in the Upper Room Library. In 1842, there was still a provision on the books regarding class meetings stating that persons who willingly neglected these meetings should be reminded that doing so meant they could be excluded from the church. What's less than clear, though, is that anyone would actually follow through on such accountability. In 1848 in the MEC (North), there was not only no reference to this provision for continued attendance in class meetings after the 6 month trial period, but also no identified "section" on class meetings at all. And there was also an addition made to the ways persons could become members. If they were part of any other "orthodox" church, they could be admitted with no trial period, provided they could answer doctrinal questions and "other considerations" (not clearly specified) suitably. Both of these changes are also included in the 1857 Discipline of the MECS (South).

Scott Kisker has documented both this decline of discipline and the some of the historical forces at work that led to it in his little book, Mainline or Methodist. To his insights, I add an ecclesio-sociological one that to the degree that the former Methodist societies were living into their new identities as "congregations" like the other congregations of their era-- that is as fundamentally the public institutional expression of Christian community-- their capacity to continue to support these non-public and rather counter-cultural "little cells of practiced believers" as the norm for congregational membership-- congregations full of real Christians-- was increasingly compromised.

So, while the mix of things in the early 19th century for Methodists might look like this:

Worship:

Sunday Morning (Thinning but Sacramentally Thick Practices, Some "Fix" in Preaching)

Sunday Evening: Some "Fix" in exhortation, more expressive practices overall

Thursday Evening: Small-group, face-to-face community practices of scripture reading, prayer and holy conversation

Discipleship:

Sunday Evening: Purpose of gathering was as "mid-size group" experience to encourage and exhort people to growth in holiness and practice in their daily lives (i.e., support system for class meetings, connection to other societies)

Thursday Evening: Accountability for practices actually engaged (or not engaged) throughout the previous week, and face to face support to improve the coming week

By the 1830s, the peak of revivalism, and fully instantiated in the Discipline by the end of the 1840s, the relationships looked like this:

Worship:

Sunday Morning: Even thinner, though still sacramentally "thick" practices, but worship really as a means to another end-- seeking or getting new members into the six month waiting process, if not admitting them on the spot (though this wasn't quite sanctioned!).

Sunday Evening: Mostly "fix" for those who still attended.

Thursday Evening: Probably no longer happening.

Discipleship:

Sunday Evening: Since the class meetings were essentially rare or non-existent, the discipleship focus of activities here began to "drift"

Thursday Evening: Not happening.

Sunday Schools: Initially to train children in literacy and Bible, but over time a variety of functions for adults and children alike

Women's Society Meetings: Women learning about and engaging in a variety of mission and charity-related activities

How Did We Get from There to Here?

Stay tuned for part 6-- coming soon!