History of Hymns: 'Amazing Grace' Part II

By C. Michael Hawn

“Amazing Grace”

by John Newton

The United Methodist Hymnal, 378

Faith’s Review and Expectation.—I Chron. xvii. 16, 17.

2. ‘Twas grace that taught my heart to fear,

And grace my fears relieved;

How precious did that grace appear,

The hour I first believed!

3. Through many dangers, toils, and snares,

I have already come;

‘Tis grace has brought me safe thus far,

And grace will lead me home.

4. The Lord has promised good to me,

His word my hope secures;

He will my shield and portion be,

As long as life endures.

5. Yes, when this flesh and heart shall fail,

And mortal life shall cease;

I shall possess, within the veil,

A life of joy and peace.

6. The earth shall soon dissolve like snow,

The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call’d me here below,

Will be for ever mine.

This discussion of “Amazing Grace,” one of the most prominently recognized and most often sung hymns in the world, is a continuation from an earlier History of Hymns column. To read “Amazing Grace”: Part I, see the following link: https://www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/history-of-hymns-amazing-grace-part-i

“Amazing Grace,” Stanzas 2-6

A quick reading of stanzas 2-6 as they appear in their original publication, the Olney Hymns (1779), may be informative for many readers. Stanzas 2 and 3 appear in virtually all hymnals, and some include stanza 4. Few hymnals produced in the United States include stanzas 5 and 6.

Stanzas 1 and 2 address the first large section of Newton’s New Year’s Day sermon in 1773: “Who am I?” Stanza 2, cited above, seems to have been drawn from Newton’s sermon that day (see: https://www.johnnewton.org/Groups/231011/The_John_Newton/new_menus/Amazing_Grace/sermon_notes/sermon_notes.aspx):

1.2 “Rebellious. Blinded by the god of this world. We had not so much a desire of deliverance. Instead of desiring the Lord's help, we breathed a spirit of defiance against him. His mercy came to us not only undeserved but undesired. Yea [a] few [of] us but resisted his calls, and when he knocked at the door of our hearts endeavoured to shut him out till he overcame us by the power of his grace.”

Stanzas 3 and 4 relate closely to part 2 of the sermon of the day, “That thou hast brought me hitherto”. A particular sentence in the Scripture of the day is relevant here: “Who am I, O Lord God, and what is mine house, that thou hast brought me hitherto?” (I Chronicles 17:16) Newton’s brief notes on this section follow:

“Here let us look back: 2.1 Before conversion His providential care preserving us from a thousand seen, millions of unseen dangers, when we knew him not. His secret guidance, leading us by a way which we knew not, till his time of love came.”

While it may be overreaching to ascribe too much direct autobiographical influence in this hymn, one can well imagine that Newton may have inserted an example from his days as a seafaring captain with a cargo of enslaved Africans weathering stormy seas that threatened the lives of all on board. Indeed, it is likely that Africans were lost on every middle passage voyage from their homeland to the New World. By the mid-1740s, Newton was reading the influential devotional book, The Imitation of Christ (ca. 1418-1427) by German Catholic monk Thomas à Kempis (c. 1380-1471), a turning point in Newton’s spiritual life. For a brief overview of Newton’s life and a description of a particular storm in 1747, see http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/pastorsandpreachers/john-newton.html. The first three stanzas cite the word “grace” six times.

Stanza 4, “The Lord has promised good to me,” rounds out the two stanzas addressing art 2 of the sermon outline: 2:3 “Mercy and goodness have followed us. In temporals, he has led and fed us.”

The original stanzas 5 and 6 are the least known and rarely appear in current hymnals in the USA. The United Methodist Hymnal (1989) is unusual in that it includes five of the original six stanzas virtually intact. These last two stanzas parallel part 3 of the sermon: “You have spoken about the future.”

Perhaps, most surprising, is the awareness of the oft-printed final stanza in hymnals in the United States, which was not part of the original hymn:

When we’ve been there ten thousand years,

Bright shining as the sun,

We’ve no less days to sing God’s praise

Than when we’ve first begun.

Rarely, if ever, used in English language hymnals outside the United States, this stanza was located in A Collection of Sacred Ballads (1790), where it was appended to “Jerusalem, My Happy Home” (Anon., c. 1580). American gospel song composer, E. O. Excell (1851-1921) is credited with attaching this stanza to the end of Newton’s “Amazing Grace” in his Coronation Hymns for the Church Sunday School (Chicago, 1910). A common practice during the nineteenth-century revival collections was to freely borrow refrains and stanzas from other sources and integrate them into existing hymns, sometimes known as “wandering” or “floating” stanzas or refrains. Obviously, stanza 6 of the original hymn covers some of the same theological territory, that of eschatology or heaven, but it contains a possible Calvinist interpretation of election in the third line of this stanza — “God, who called me here below.” Since the revival movement was largely Armenian in theology or salvation open to all, this may have rendered the original stanza 6 unacceptable. Furthermore, the language of the borrowed stanza is more direct for American ears, though something is lost by omitting the compelling images in Newton’s original: “The earth shall soon dissolve like snow,/The sun forbear to shine.”

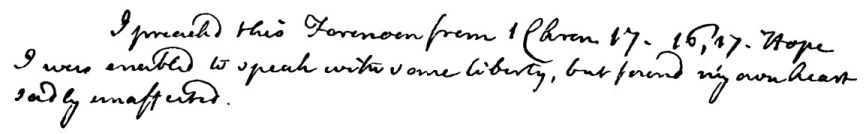

Newton leaves us a curious note at the conclusion of his sermon in his own hand:

“I preached this Forenoon from 1 Chron. 17.16.17. Hope I was enabled to speak with some liberty, but found my own heart sadly unaffected.”

Might it be that, upon reflection, the captain of ships that transported countless enslaved Africans to a life of servitude and misery was still wrestling with the miracle of “amazing grace”?

Though it is tempting, even for this writer, to find autobiographical connections between Newton’s dramatic life story and his most famous hymn, Carl Daw, Jr. counsels us wisely:

Although modern readers and singers are more likely to look at this hymn for points of connection with Newton’s own eventful history as a former sailor and slave trader turned Anglican priest and abolitionist, the author himself probably thought of what he had written as an outline of the typical journey from utter despair (1.2, “a wretch like me”) to confident faith (3.4, “grace will lead me home”). That assumption of speaking to a general human condition accounts, at least partly, for the widespread use of this hymn. . .” (Daw, 617).

The Music of “Amazing Grace”

Newton’s text was first paired with a variety of tunes including ARLINGTON, WARWICK, HEBER, and BELMONT in hundreds of hymnals. The tune that we know first appeared in two different versions in the Columbian Harmony (Cincinnati, 1829) edited by Benjamin Shaw and Charles H. Spilman, with the tune names St. Mary’s and GALLAHER. Later collections picked up the tune, but paired its frequently used Common Meter (8.6.8.6) structure to other texts, such as in the Virginia Harmony (1831) where it was named HARMONY GROVE. Finally, William (“Singing Billy”) Walker (1809-1875) paired the tune with Newton’s text in his famous collection Southern Harmony (New Haven, 1835) under the name NEW BRITAIN. Edwin O. Excell, the same composer who solidified the use of the alternate final stanza to the hymn, included the tune under the title AMAZING GRACE in his collection Make His Praise Glorious (1900). The arrangement of the tune that is found in many current hymnals first appeared in Coronation Hymns (1910). The United Methodist Hymnal uses the harmonization found in the first (1900) of Excell’s two collections. It was not until the 1960s that AMAZING GRACE (NEW BRITAIN) was accepted as the primary tune associated with this text beyond the United States.

“Amazing Grace” in Other Cultural Contexts

The United Methodist Hymnal published anonymous phonetic transcriptions of a stanza in four Native American languages (Cherokee, Kiowa, Creek, and Choctaw) that are sung to the tune of AMAZING GRACE. A Navajo text by Albert Tsosie was added to these. These texts are not translations of Newton’s text, but are anonymous (except for the Navajo stanza) stanzas on the Second Coming, reflecting more closely the theme of the anonymous final English-language stanza appended later to Newton’s text (Young, 207). A similar approach was taken in the Presbyterian Church (USA) hymnal Glory to God (2013).

The range of musical styles that incorporate at least a portion of Newton’s text is truly astounding and perhaps unparalleled in Christian hymnody. The appearance in William Walker’s Southern Harmony was a cultural adaptation to the shape-note tradition with a distinctive sound. Note the African American “Dr. Watts Metered” style transcribed by Evelyn Simpson-Curenton for the African American Heritage Hymnal (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2001) https://hymnary.org/hymn/AAHH2001/page/393. More recently, Chris Tomlin’s (b. 1972) “Amazing Grace (My Chains Are Gone)” alludes both to the autobiographical context of slavery and to the universal understanding of the power of salvation through grace to free us from all forms of bondage, with the addition of the refrain “My chains are gone.” The YouTube clip cited intersperses scenes from the British-Nigerian film Amazing Grace (2006) about the abolition of slavery in the British Empire led by William Wilberforce (See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y-4NFvI5U9w).

Most recently, President Obama sang, perhaps spontaneously, “Amazing Grace” at the June 17, 2015, Charleston church shooting, a mass shooting by a young white supremacist that killed nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. (See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IN05jVNBs64.) Words cannot describe the power of this hymn sung by the first African-American president in a city where the sale of enslaved Africans was once a common commercial transaction.

Perhaps the greatest enigma of this hymn is that “Amazing Grace” speaks globally of the mystery of salvation without mentioning the name of Jesus. Much like Sydney Carter’s “Lord of the Dance” (1963), an allegory on the life of Christ that never mentions Jesus, it has a witness well beyond Christian circles. The universality of this hymn lies in our awareness of the wretchedness of the human condition and for a hope deeply embedded in humanity at large that we may be “saved” from that condition by something beyond ourselves — “Amazing Grace.”

FURTHER READING AND REFERENCES

- Carl P. Daw, Jr. Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2016), 616-618.

- “John Newton: Reformed Slave Trader,” Christianity Today, http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/pastorsandpreachers/john-newton.html.

- Marylynn Rouse, Transcription from Princeton University Library, John Newton Diary, CO199 (2000): https://www.johnnewton.org/Groups/231011/The_John_Newton/new_menus/Amazing_Grace/sermon_notes/sermon_notes.aspx.

- Carlton R. Young, Companion to The United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993), 206-208.

C. Michael Hawn, D.M.A., F.H.S., is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music and Adjunct Professor and Director, Doctor of Pastoral Music Program at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University.

Contact Us for Help

View staff by program area to ask for additional assistance.