History of Hymns: 'Christ for the World We Sing'

By C. Michael Hawn

“Christ for the World We Sing”

By Samuel Wolcott

The United Methodist Hymnal, 568

Christ for the world we sing,

the world for Christ we bring,

with loving zeal;

the poor, and them that mourn,

the faint and overborne,

sinsick and sorrowworn,

whom Christ doth heal.

An interesting subgenre of Christian hymnody is made up of those hymns devoted to Christian missions. “Christ for the World We Sing” (1862) by American Congregational minister Samuel Wolcott (1813-1886) is a representative example. It captures the zeal and fervor of the movement found both in Great Britain and the United States during the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth centuries. Others in this genre include “Heralds of Christ” (1915) by Laura Copenhaver to the stirring tune NATIONAL ANTHEM (The United Methodist Hymnal, 567), “We’ve a Story to Tell to the Nations” (1896) by H. Ernest Nichol (The United Methodist Hymnal, 569) with its march-like refrain reminiscent of “Onward Christian soldiers” and “Go, Make of All Disciples” (1955) by Leon Adkins to the uplifting LANCASHIRE (The United Methodist Hymnal, 571).

Together, these hymns offer sung responses to the Great Commission, Matthew 28:16-20:

Then the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain where Jesus had told them to go. When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted. Then Jesus came to them and said, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely I am with you always, to the very end of the age (NIV*).

These words, recorded at the end of Matthew’s Gospel immediately following the writer’s account of the Resurrection, have inspired many to respond to the vocation of “foreign missions,” claiming the promise of Acts 1:8: “. . . you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (NIV*).

Indeed, these hymns offer a counterbalance to the more personal gospel songs with their focus on an individual relationship with Christ. Whereas many of these gospel songs, composed on both sides of the Atlantic, viewed Jesus as a personal companion on the journey, the great mission hymns present Christ as the triumphal monarch who claims all earth as his domain, a vision to be fully realized in heaven as described in Revelation 7:9: “After this I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands” (NIV*).

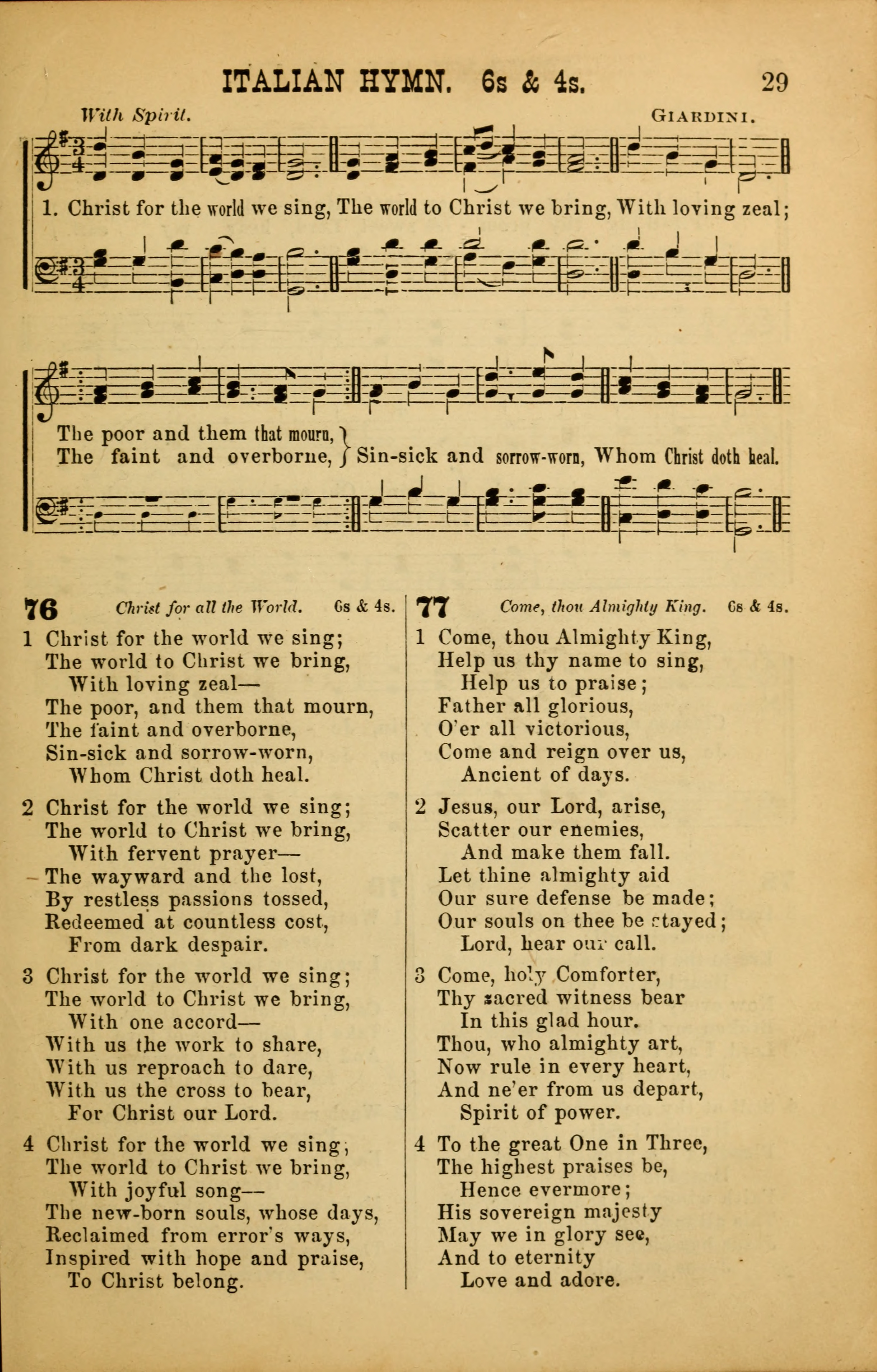

Hymns such as these provided powerful encouragement to young people who, claiming the mandate of Matthew 28 and the empowerment of Act 1, responded to the call. Such was the context of the composition of “Christ for the World We Wing.” The hymn’s origins can be found in a Y.M.C.A. convention held in Cleveland, Ohio, on February 7, 1869, where the theme was “Christ for the world, and the world for Christ.” Evergreen branches spelled out these words on the stage above the speaker’s podium. Samuel Wolcott, pastor of Plymouth Congregational Church in Cleveland, returned to the parsonage after reflecting on the theme and wrote this text. It was paired to ITALIAN HYMN (associated with “Come, Thou Almighty King”) by noted gospel song composer William H. Doane (1832-1915) and soon afterward appeared under an ambitious title in Doane’s Songs of Devotion for Christian Associations: a collection of psalms, hymns, spiritual songs, with music for church services, prayer and conference meetings, religious conventions, and family worship (1870) as hymn 76.

Within two decades, the hymn was appearing in denominational hymnals in the U.S.A.; by the 1920s, it was included in hymnals in Great Britain.

Stanzas 1 and 2 depict a world in need of Christ, including “the poor and them that mourn,” an allusion to the Beatitudes (Matthew 2:3-4); “the faint and overborne”; numerous passages encourage Christ’s followers to not be faint-hearted, including I Thessalonians 5:14, Galatians 6:9, and Hebrews 12:3; and those who are “sinsick and sorrowworn,” figures of speech that have a long history in hymnody in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The “loving zeal” of stanza 1 is undergirded by “fervent prayer” in stanza 2. Those in need include “the wayward and the lost” who must be “redeemed at countless cost, from dark despair.”

Stanza three calls for unity – “one accord” – in responding to this call: “the work to share” and “the cross to bear, for Christ our Lord.” The final stanza focuses on the spirit of “joyful song” as “newborn souls . . . [are] reclaimed from error’s ways, / inspired by hope and praise, / to Christ belong.”

Wolcott, a native of Connecticut, was a graduate of Yale College and Andover Theological Seminary. He served as a missionary in Syria for two years (1840-1842), returning home after ill health. Ordained as a Congregational minister, he served congregations in Providence, Rhode Island; Chicago, Illinois; and finally Cleveland, Ohio, where, in addition to pastoring Plymouth Congregational Church, he became secretary of the Ohio Home Missionary Society. His interest in hymns was not apparent until he was 56 years old; but from that time, he wrote more than 200, of which “Christ for the World We Sing” is the only one that is still sung. Hymnologist Albert Bailey said of this hymn, “The sentiment is praiseworthy but the poetry is inferior” (Bailey, 502).

Triumphal mission hymns run concurrently with those inspired by the social gospel of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Social gospel hymns, many inspired by the theology of Baptist minister Walter Rauschenbusch (1861-1918), address the needs of the cities, especially during the industrial revolution. These include Congregational minister Washington Gladden’s (1836-1918) “O Master, Let Me Walk with Thee” (1879) and Methodist minister Frank Mason North’s (1850-1935) “Where Cross the Crowded Ways of Life” (1903). The tone of these hymns is more humble and prayerful, both in text and musical settings. Rather than a militant mission to claim the world for Christ’s kingdom, these hymns invite the singer to accompany Jesus in his ministry to those in need in the heart of the city. Together, mission and social gospel hymns span the gamut of evangelical outreach between what denominations used to call “foreign” and “home” missions.

“Making disciples” is not for the fainthearted or the insecure. It is a dangerous and complex calling. Like many parts of Scripture, even the Great Commission can be abused when taken out of context. While the sacrifice, courage, and passion of missionaries of this era, or any era, would be hard to question, the gospel cannot be shared from one group to another in a pure form untainted by cultural associations, political entanglements, and personal prejudices. It is an astute missionary who understands how the gospel message of good news may be communicated within the mores of a specific culture and its expectations. It is an astute missionary who can live beyond provincial nationalism and allegiance to his/her native country, and love the culture and ways of another. It is an astute missionary who can set aside, at least in part, the perceptions that have framed an understanding of how God moves and works in the world since his/her birth, and find beauty and value in another culture’s way of perceiving the world. The history of Christian missions is replete with the witness of missionaries who walked gracefully among those in the broader human family in love and companionship and those who charged into the fray to right wrongs and set records straight, and in doing so, have left a path of detritus littered with bitterness, judgmentalism, colonialism, and triumphal imperialism.

With gratitude for the devotion, sacrifice, and vision of the missionaries who endured untold hardships to respond to the mandate of Matthew 28 in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and appreciation for the “harvests” that resulted from their work, at least two questions arise for us today: (1) Has this form of Christian missions produced self-sustaining and culturally sensitive manifestations of Christ’s presence in their locations? (2) Will this triumphal approach to Christian witness worldwide work today in a global environment that is increasingly suspect, even defiantly resistant, to forms of faith tinged with Western cultural and nationalistic imperialism?

British hymnologist Erik Routley (1917-1982) suggested in 1959 that mission hymnody should give way to what he called “ecumenical” hymnody – hymns from former “mission fields” that can inform and broaden our faith and provide congregational song for the ecumenical church – not the church of all denominations, but, according to the Greek root of the word, the church of the “whole inhabited earth” (Routley, 17). Citing Wolcott’s hymn, Canadian scholar Lionel Adey notes how the “sacred poets [of this era] blended the patriotic with the social and religious spirit of mission . . . while ministering to ‘the poor and them that mourn’” (Adey, 154-155). Perhaps we should acknowledge the great mission hymns of the past for the role they played in motivating those who responded in good faith to Mathew 28 in their day, set them aside, and create new hymns for a world in need that reflect more of the humility of those composed for the city. If we listen closely enough, we may find that those to whom we would minister around the world have already written their own songs that can teach us how to be in community with them.

NOTE: The author is grateful for conversations with Dr. Becca Whitla on issues related to the complexity and legacy of mission hymns.

For Further Reading

Lionel Adey, Class and Idol in the English Hymn (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1988).

Albert E. Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950).

Erik Routley, Ecumenical Hymnody (London: Independent Press Ltd., 1959).

J. Richard Watson and Carlton Young. "Christ for the World We Sing." The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology. Canterbury Press, accessed March 28, 2019, http://www.hymnology.co.uk/c/christ-for-the-world-we-sing.

Becca Whitla, “Hymnody in Missionary Lands: A Decolonial Critique,” Hymns and Hymnody: A Legacy of Hymnists, edited by Benjamin K. Forrest, Mark A. Lamport, and Vernon M. Whaley (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, Wipf and Stock, forthcoming).

Bible verses marked NIV are from the New International Version (NIV)

Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

C. Michael Hawn, D.M.A., F.H.S., is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music and Adjunct Professor and Director of the Doctor of Pastoral Music Program at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University.

Contact Us for Help

View staff by program area to ask for additional assistance.