History of Hymns: 'Kum Ba Yah'

By C. Michael Hawn

“Kum Ba Yah” (“Come by Here”)

African American Spiritual

The United Methodist Hymnal, 494

Kum ba yah, my Lord, kum ba yah.

Kum ba yah, my Lord, kum ba yah.

Kum ba yah, my Lord, kum ba yah.

Oh, Lord, kum ba yah.

The origins of this song have been enveloped in mystery for nearly a century. Some have said that it came from Africa. Others have claimed authorship and even copyrighted it. Some grew up singing it around campfires at summer camp accompanied by folk guitar and three chords. It has been sung at protest marches and candlelight vigils. Those who came of age during the 1960s and 1970s during the Viet Nam War heard Joan Baez (b. 1941) and Pete Seeger (1919-2014) sing this song, as well as Odetta (1930-2008) and the all-women, African American a cappella ensemble, Sweet Honey in the Rock. Indeed, “Kum ba yah” was considered to be a significant Civil Rights song by protestors (Spencer, 93).

Many recall the experience of a “Kum ba yah” moment – a fleeting feeling of unity or togetherness solidified while singing together. Sometime after the 1980s and into the current century, “Kum ba yah” began to be viewed as a simplistic children’s song, and the unified feelings it once symbolized became a sonic metaphor for cultural naïveté in a more callous and jaded era. Regardless of one’s earlier associations with this song, set them aside and take a fresh look at a spiritual that has a word for us.

African Connections

The claims to African origins come, in part, from Lynn and Katharine Rohrbaugh, leaders of the Cooperative Recreational Service in Ohio. Among their activities was the compiling of songbooks for camps in which appeared “Come by Here” in a 1955 collection. They received the song from Melvin Blake, a missionary who had returned from Angola. Their first printings spelled the name of the song “Koombaya” rather than “Come by yah.” Later they changed the spelling so that it sounded more like “Come by here.” However, the song had caught on under its earlier pronunciation. The Rohrbaughs collected a second version from Van Richards, a Liberian student at Ohio State, and published that version in anther collection. As a result, during the early years of its popularity, many people assumed the song had African origins and that the term “Kumbaya” was a vague African dialect.

Martin V. Frey

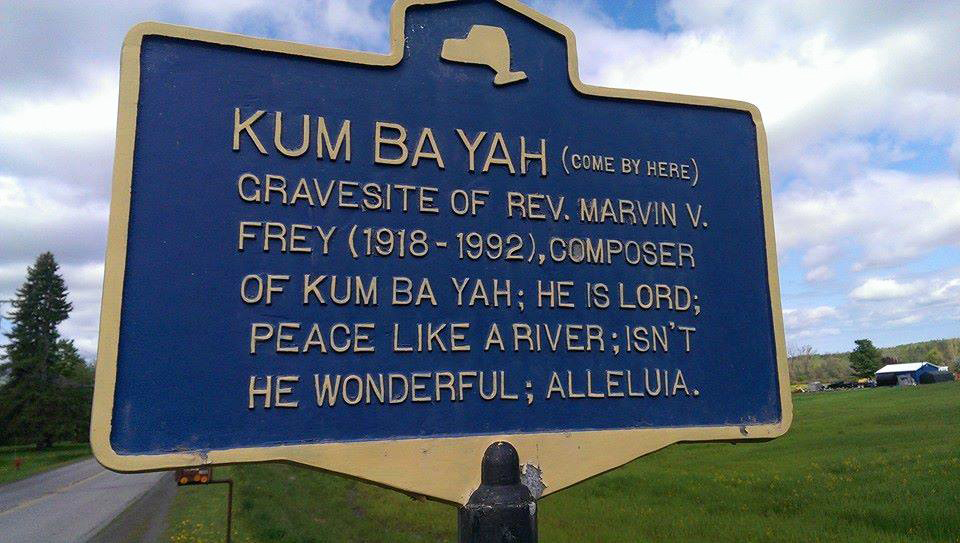

Then there was the claim by an Oregon evangelist, Rev. Martin V. Frey (1918-1992), who said he composed it in 1936 and included it in his informal Revival Choruses of Martin V. Frey (Portland, 1939), though he did not copyright it until the 1970s. Stephen Winick, editor at the Library of Congress Folklife Center since 2005, notes that Frey “was a colorful character who in the 1970s decided to claim copyright on a bunch of spirituals, and who knows if he really wrote any of them?” (Fenn, Podcast Transcript, n.p.). Among those commonly known spirituals for which Frey claimed authorship was “Do Lord, Do Remember Me” and “Peace Like a River.” A historic marker in New York perpetrates this misconception:

|

| Photo by Michael Reese of a marker near Martin V. Frey's gravesite in the West Barre Cemetery in Orleans County, New York. |

I have encountered other songs in which an author claimed sincerely to have composed it, but whose authorship was later proven erroneous. Indeed, some serious scholars, predating Winick’s scholarship, have bestowed authorship to Frey (see VanDyke, 60). When asked directly if Frey was lying, Winick, responded as follows:

Well, I wouldn't say that. He claimed that he based the song on a spoken prayer he heard in Oregon, and it's certainly possible that his memory was somewhat faulty. That he actually heard a sung version, and then adapted it. Most songwriters have had that experience of thinking they wrote a melody and then realizing it was something they had heard (Fenn, n.p.).

Pete Seeger offered this generous appraisal of Frey’s claim of authorship:

You should know that . . . if you don't know it already . . . that many times songwriters think they have written a melody, and they're only remembering an old melody from years before. It happened to the man who thought he wrote "Kumbaya," "Come by Here, Lord." He wrote it as a slow processional (cited in Fenn, n.p.).

“Kum ba yah” Moments

The backlash associated with the song during the last three decades is a curious turn of events. Stephen Winick summarizes this well:

Politically, [“Kumbaya”] became shorthand for weak consensus seeking that fails to accomplish crucial goals. Socially, it came to stand for the touchy-feely, the wishy-washy, the nerdy, and the meek. These recent attitudes toward the song are unfortunate, since the original is a beautiful example of traditional music, dialect, and creativity. However, the song’s recent fall from grace has at least added some colorful metaphors to American political discourse, such phrases as “to join hands and sing ‘Kumbaya,'” which means to ignore our differences and get along (albeit superficially), and “Kumbaya moment,” an event at which such naïve bonding occurs (Winick, n.p.).

Robert Winslow Gordon

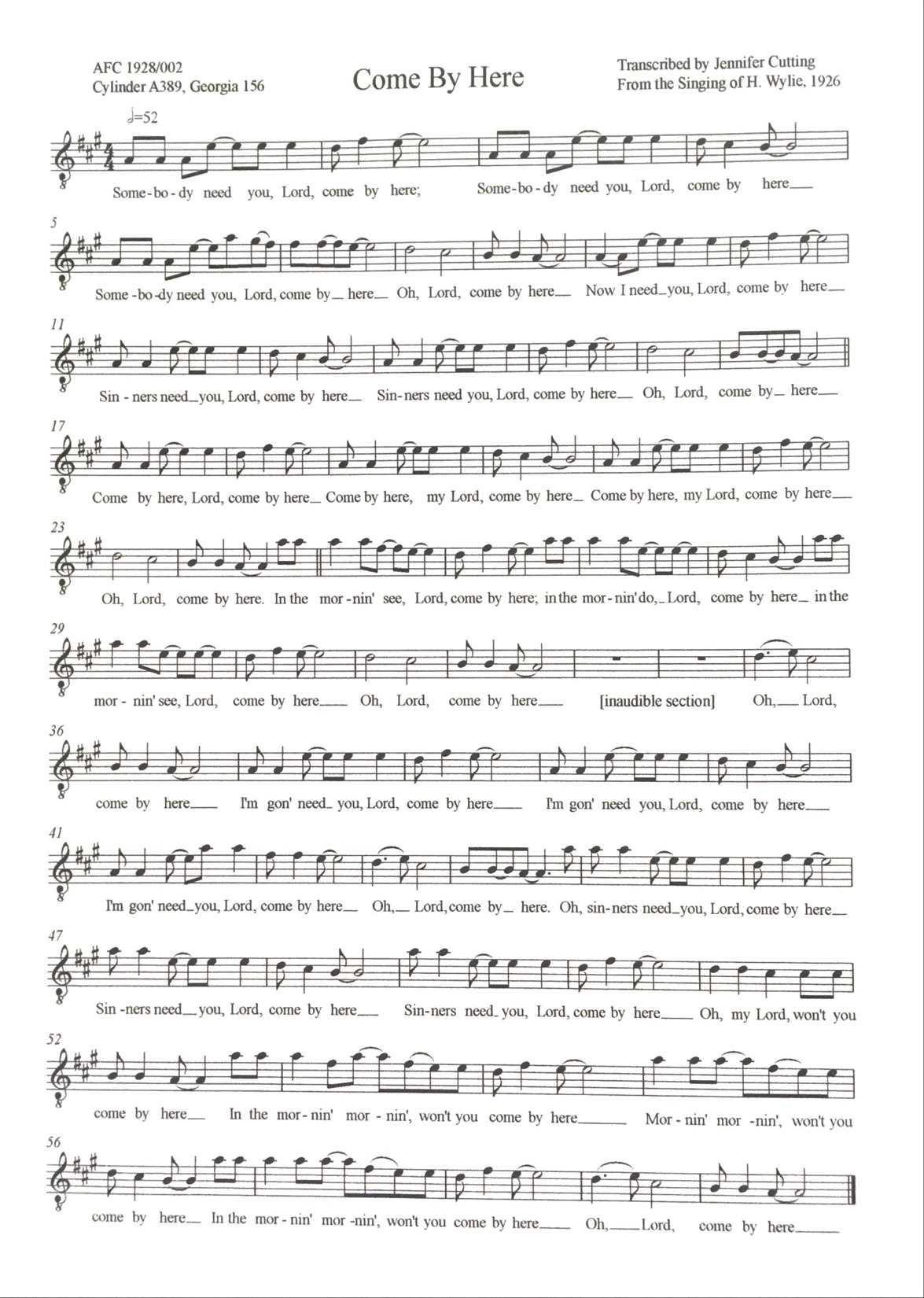

Things may be changing, however. Stephen Winick’s recent research has done much to change this view. The most likely origins of the song as we have come to know it may reside in the Sea Islands of Georgia, where an early cylinder recording made by Harvard-educated, folk-song collector Robert Winslow Gordon (1888-1961) made history. Gordon, a faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley, recorded by Africa American “H[enry] Wylie” in Darien, Georgia during April 17, 1926, the earliest audio rendition: https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197143?loclr=blogflt. A transcription of this recording by Jennifer Cutting follows:

While the English text and syncopated melody differ from popular renditions or those that generally appear in hymnals, it is unmistakably a regional version of the same song.

This 1926 recording and subsequent research in this century have served several purposes. First, such research would seem to discredit Frey’s authorship and establish the probable origins of the spiritual on the islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, where the Gullah dialect (also known as the Sea Islands Creole dialect) was spoken by enslaved Africans in that region. “Kum by yah” is a Creole version of “come by here.”

Julian Parks Boyd

Coincidentally, a manuscript acquired in February 1927 by historian and folklore collector Julian Parks Boyd, founder of the archive at the American Folklore Center in North Carolina, indicates that awareness of “Come by Here” extended beyond the Gullah region. Other recordings and versions suggest that the spiritual had a life throughout the south and as far west as Texas. The song first appeared in a collection published by the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals in a version titled “Come by Yuh.” The collection, titled The Carolina Low Country (New York, 1931), edited by Augustine T. Smith, et al., does not date the song, but all the songs in the book were collected between 1922 and 1931 (Winick, n.p.). It is likely that this song with the refrain “Come By Yuh, Lord, come by Yuh,” as well as a stanza “somebody need you lord, com by yuh” is the same song recorded by Gordon. Following Gordon’s 1926 recording, the song had been recorded or transcribed by at least five singers as well as other similar songs that appear or have been influenced by it.

“Kum ba yah” Today

Winick’s research indicates that the spiritual’s origins are indeed complex and fascinating:

[Research] suggests that “Kumbaya” is an African American spiritual which originated somewhere in the American south, and then traveled all over the world: to Africa, where missionaries sang it for new converts; to the northwestern United States, where Marvin Frey heard it and adapted it as “Come By Here”; to coastal Georgia and South Carolina, where it was adapted into the Gullah dialect. It was likely versions in Gullah Geechee dialect that made it to the Northeastern United States, where it entered the repertoires of such singers as Pete Seeger and Joan Baez; and eventually to Europe, South America, Australia, and other parts of the world, where revival recordings of the song abound (Winick, n.p).

Wisnick’s research led to the Georgia State legislature adopting “Kumbaya” as the first official state historical song in March 2017. Based on their reading of the research by the Library of Congress and the Archive of American Folk-Song, the Georgia legislature concluded that all significant touchpoints of the spiritual were in Georgia, including Gordon’s recording of Wylie, “an African American of Gullah-Geechee heritage.” The resolution concludes, “THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE that the members of this body recognize this historical song of Georgia and its significance to our state and to the Gullah-Geechee culture.” The documentation of this historic act may be found on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwNmWHQjg8I.

Versions of “Come by Here”

Because of its repetition and structural flexibility, numerous textual variations of the spiritual exist. Standard stanzas in hymnals today include:

Someone’s praying, Lord . . .

Someone’s crying, Lord . . .

Someone needs you, Lord . . .

Someone’s singing, Lord . . .

The United Methodist Hymnal adds, “Let us praise the Lord . . .”

The focus of the stanzas in current hymnals, however, seems to have changed from the earlier versions. In the 1926 recording by H. Wylie cited above, the stanzas are:

Somebody need you, Lord . . .

Now I need you, Lord . . .

Sinners need you, Lord . . .

Come by here, Lord . . .

In the mornin’, Lord . . .

I’m goin’ need you, Lord . . .

A recording by folksong collector Alan Lomax (1867-1948) in May 1936 in Railford, Florida, includes the following stanzas:

Come by here, my lord, come by here

Well we [down in?] trouble, Lord, come by here

Well, it’s somebody needs you lord, come by here

Come by here, my lord, come by here

Well it’s somebody sick Lord come by here

Well, we need you Jesus Lord to come by here

Come by here, my lord, come by here

Somebody moanin’, Lord, come by here

The Library of Congress recording by Ethel Best supported by an unidentified chorus may be heard at: https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197362/?loclr=blogflt.

Reconceiving “Kum ba yah”

It appears that earlier stanzas were much more explicit in addressing people in need—both physically and spiritually. Indeed, these stanzas call to mind times in Christ’s ministry when he came to specific places for healing and raising the dead. In general, we find that Jesus traveled far and wide and that crowds followed him:

Jesus went throughout Galilee, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom, and healing every disease and sickness among the people. News about him spread all over Syria, and people brought to him all who were ill with various diseases, those suffering severe pain, the demon-possessed, those having seizures, and the paralyzed; and he healed them (Matthew 4:23-24, NIV*).

Jesus’ ministry was one of being present in the lives of people. A short list of Jesus’ actions where he “came by here” to heal physical and spiritual illnesses follows:

- Healing a woman with an issue of blood (Luke 8:43-48)

- Healing a man born blind (John 9)

- Healing a crippled man (Matthew 9:1-4)

- Casting out demons (Matthew 8:28-34; Mark 5:1-20; Luke 8:26-33)

- Raising of Lazarus (John 11:1-40)

United Methodist seminary professor William B. McCain affirms the significance of the presence of God in African American worship:

One of the most distinctive characteristics of worship in the black community has been the overwhelming sense of God’s actual presence among the faithful. Black people have always trusted Jesus’ promise in Matthew 18:20 that, “where two or three are gathered in my name, there I am in the midst of them.” [KJV] As the slaves met for worship, often under the cover of darkness, first on their agenda was to invoke the presence of the Lord by softly and reverently chanting “Kum Ba Yah” . . . (McLain, 112-113).

Those who reduce this spiritual to a “feel-good moment” of ephemeral togetherness or cynically see it as simplistic and shallow in the current cultural and political context should call to mind the witness of Jesus, the Christ, who was present with those in times of need and promises to be with us always (Matthew 28:20). In addition, we should not be hesitant to incorporate specific instances of human need into the stanzas rather than relying only on the more generic stanzas that we find in current hymnals.

Finally, I would suggest that rather than the slow folk-like campfire version, we reclaim the more rhythmic syncopated earlier versions found in the recordings linked to this article. These engage the singer with more energy and, with a little imagination, encourage rhythmic hand clapping, light drumming, and swaying.

Carl P. Daw, Jr. confirms my conclusions:

Despite . . . “cultural despisers” (as Friederich Schleiermacher would call them), this spiritual retains much power in the context of a worshiping community. As a kind of macaronic text bridging languages of differing communities, it offers a more emotive expression of prayer than standard English might convey by itself. Because it is a text that allows for improvisation and expansion . . . , it has a rare potential to be engaging and inclusive (Daw, 477).

Further Reading and Sources:

“Come by Here” (“Kumbayah”), recorded by Robert Winslow Gordon, Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200197143?loclr=blogflt.

Carl P. Daw, Jr. Glory to God: A Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2016).

John Fenn, “Kumbaya: Stories of an African American Spiritual,” Folklife Today, January 2019. Transcript: http://www.loc.gov/podcasts/folklife-today/transcripts/FolklifeToday-Podcast_Episode4_transcription.pdf.

William B. McClain, Come Sunday, the Liturgy of Zion: A Companion to Songs of Zion (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1990).

Jon Michael Spencer, Black Hymnody: A Hymnological History of the African American Church (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1992).

Mary Louise VanDyke, “Research Report: Closing the Case on ‘Kum ba yah.’” The Hymn 47:3 (July 1996), 60.

Stephen Winick, “Kumbaya: History of an Old Song,” Folklife Today: American Folklife Center & Veterans History Project (February 26, 2018), https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2018/02/kumbaya-history-of-an-old-song/.

* Verses marked NIV are from the New International Version (NIV) Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

C. Michael Hawn, D.M.A., F.H.S., is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music and Adjunct Professor and Director of the Doctor of Pastoral Music Program at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University.

Contact Us for Help

View staff by program area to ask for additional assistance.