History of Hymns: 'When We All Get to Heaven'

By C. Michael Hawn

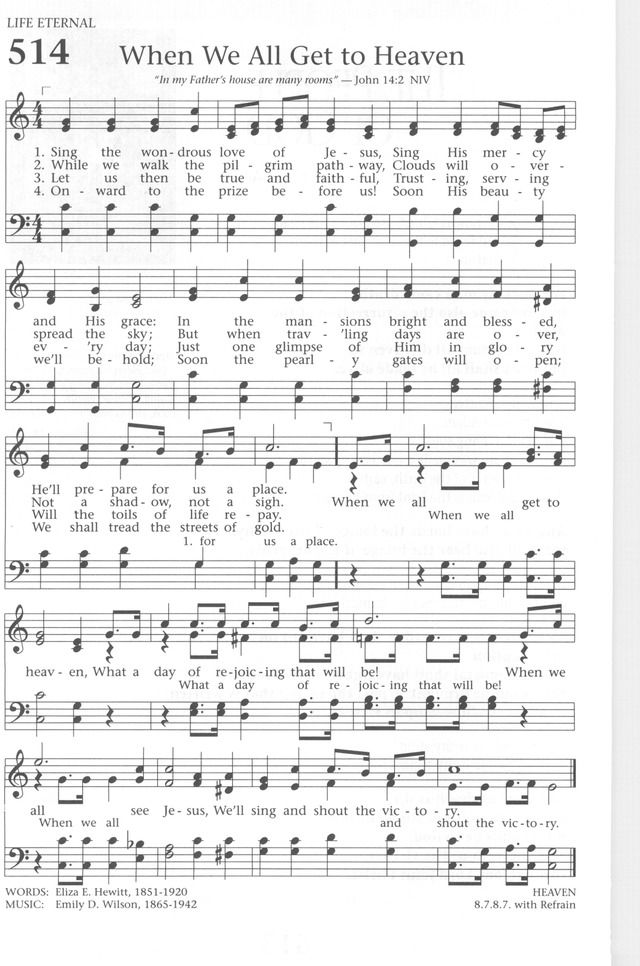

“When We All Get to Heaven”

(“Sing the Wondrous Love of Jesus”)

by Eliza E. Hewitt

The United Methodist Hymnal, 701

Sing the wondrous love of Jesus;

sing his mercy and his grace.

In the mansions bright and blessed

he’ll prepare for us a place.

Refrain:

When we all get to heaven,

what a day of rejoicing that will be!

When we all see Jesus,

we’ll sing and shout the victory!

Philadelphians Eliza E. Hewitt (1851-1920) and Emily D. Wilson (1865-1942) combined as poet and musician respectively to give us a gospel song that captures the revival spirit of the late nineteenth century in a uniquely American way.

Carlton R. Young correctly notes that this hymn should be situated in its “union of revivalism and adventism in much of post-Civil War Wesleyan preaching and worship” (Young, 699). Adventism was a product of the Second Great Awakening during the first half of the nineteenth century that peaked in the 1840s. Its proponent, William Miller (1782-1849), a Baptist preacher, espoused the belief that the second coming of Jesus Christ would take place sometime between 1843 and 1844. While that did not take place, the spirit of Adventism continued throughout the remainder of the century and was evident in many gospel songs of the era.

Many readers may have grown up singing this and other songs on a similar theme during Sunday school gatherings, Sunday evening services, or revivals. Related songs include “When the Roll Is Called Up Yonder” (1899) by James M. Black (1856-1938), “Shall We Gather at the River” (1865) by Robert Lowry (1826-1899), and “O that Will Be Glory for Me” (1900) by Charles H. Gabriel (1856-1932). Make no mistake, hymns that addressed heaven were nothing new. Many eighteenth-century hymns by Charles Wesley and others referenced heaven as our ultimate destination. The nineteenth-century gospel song, however, added a spiritual fervor undergirded by a musical vitality that gave these songs a sense of imminence and urgency that had not been experienced heretofore.

The Methodists and Baptists were the dominant sources of these songs that were often included in collections geared for use in Sunday schools and revivals. Though aligned with the Presbyterians, Eliza Hewitt’s song was a product of revivals where the author “regularly attended the Methodist camp meetings” at Ocean Grove, New Jersey (Reynolds, 194, cited in Young, 699). These “seasonal and protracted meetings [were] typical of the Wesleyan campgrounds that were formed, some continuing from earlier in the century, to embody indoors the spirit of the camp meeting” (Young, 699). The “indoor” events were extensions of the rural camp meetings of the early nineteenth century, where the conditions were much more primitive. Tents were pitched, and roughhewn benches were placed to separate men from women. In these early nineteenth-century camp meetings, denominational particularities gave way to more inclusive ecclesial gatherings that included Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and even Quakers (Lorenz, 17-19). Even more astounding in the antebellum South was the participation of both African Americans and whites. As one account notes, “The blacks were the life of the camp meeting. Nine out of ten of them would have a melodious voice for singing and praying and shouting, at a great distance from the campground” (G. W. Henry, quoted in Lorenz, 31).

While the meetings at the end of the nineteenth century at Ocean Grove were under less primitive conditions, they were still rustic with simple huts and cottages replacing tents; they were also more domesticated, though the Spirit was still evident in ways that may not have been present or even permitted in the confines of mainline church sanctuaries on Sunday morning. Carlton Young describes the setting under which Eliza Hewitt composed this song:

At Ocean Grove the author and composer viscerally, visually, and audibly experienced the thrilling, though carefully staged, anticipation of Paul’s promise to members of the Thessalonian congregation. “[We] will be caught up in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air; and so we will be with the Lord forever” (1 Thessalonians 4: 17). These first-century Christians, like the Ocean Grovers after days of hearing perdition preached, had an elevated anxiety about their status at Christ’s imminent return (Young, 699).

The Ocean Grove Camp Meeting Association remains alive and well with an active program and options for tents. See https://www.oceangrove.org.

The stanzas of “When We All Get to Heaven” are replete with biblical allusions:

In stanza 1, the phrase “in the mansions bright and blessed, / he’ll prepare for us a place” is a rephrasing of John 14:2: “In my Father's house are many mansions: if it were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you.” (KJV).

Stanza 2 reminds us that in heaven, light replaces “shadows”: “and the city had no need of the sun, neither of the moon, to shine in it: for the glory of God did lighten it, and the Lamb is the light thereof” (Revelation 21:23, KJV). Furthermore, the “sighs” of sorrow and pain will be left behind: “And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away” (Revelation 21:4, KJV).

In stanza 3, the poet notes that, “just one glimpse of him in glory / will the toils of life repay”; this phrase paraphrases I Peter 4:13, “But rejoice, inasmuch as ye are partakers of Christ's sufferings; that, when his glory shall be revealed, ye may be glad also with exceeding joy” (KJV).

Stanza 4 references “the pearly gates” and “streets of gold,” images clearly drawn from Revelation 21:21: “And the twelve gates were twelve pearls: every several gate was of one pearl: and the street of the city was pure gold, as it were transparent glass” (KJV).

Theologically, an ambiguity exists concerning the phrase, “When we all get to heaven. . .” It could be a Methodist use of “all,” growing out of the Arminian inclusivity of God’s grace in the Wesleyan tradition versus the “limited atonement” of Calvinism. It could also be more of an existential statement about those gathered at Ocean Grove with the assumption that they were all going to heaven. More than likely, rather than a nuanced theological assertion, this is an eschatological hope born of revivalistic emotionalism and hyperbole.

The song was first included in Pentecostal Praises (1898), a compilation by a noted gospel song composer, William J. Kirkpatrick (1838-1921), and Henry L. Gilmour (1836-1920), for decades a choir director at camp meetings.

Eliza Edmunds Hewitt lived in Philadelphia her entire life. She was the valedictorian of her class at the Girls’ Normal School, where she taught for some years. Hewitt was prominent in the Sunday school movement, devoting time to youth at the Northern Home for Friendless Children; at Calvin Presbyterian Church, she served as the Sunday school superintendent. In spite of a spinal illness that kept her homebound for some years, she studied English literature and authored several hundred texts. The most published of her hymns, in addition to “When We All Get to Heaven,” include “There Is Sunshine in My Soul Today” (1887) and “More about Jesus Would I Know” (1887), the latter hymn appearing in The Cokesbury Hymnal (1923, No. 94). She wrote texts for some of the prominent gospel song composers of the day, including B. D. Ackley (1872-1958), Charles H. Gabriel, E. S. Lorenz (1854-1942), Homer Rodeheaver (1880-1955), and John R. Sweney (1837-1899).

Emily Divine Wilson (1865-1942) was also a life-long Philadelphian. The wife of a Methodist minister, she often attended Ocean Grove with her husband John G. Wilson. The minutes of the Philadelphia Methodist Conference noted:

Mrs. Wilson was the acknowledged inspiration of her esteemed husband. She was beloved by the congregations of the churches served. Her musical ability was a great contribution to the local church, together with her ability in dramatic art (Leon T. Moore, quoted in Reynolds, 465).

The tune name HEAVEN was ascribed to Wilson’s music by the editor of the Baptist Hymnal (1956). Of this tune, Carlton R. Young notes, “The Sunday school marching tune portrays the church, its mission, and the role of the faithful Christian progressing towards a goal. . . It is a useful genre of Christian music whereby the faithful are assured the church is on the move, irrespective of reality” (Young, 699-700). The following rendition is the original quartet version (taken from The Baptist Hymnal, 1991) that shows the independent lower voices echoing the text of the melodic line in the refrain, a characteristic of many revival songs of this day.

Further Reading and Sources:

Ellen Jane Lorenz, Glory, Hallelujah! The Story of the Campmeeting Spiritual (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1978).

William J. Reynolds, Companion to Baptist Hymnal (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1976).

Carlton R. Young, Companion to The United Methodist Hymnal (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1993).

C. Michael Hawn, D.M.A., F.H.S. , is University Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Church Music and Adjunct Professor and Director of the Doctor of Pastoral Music Program at Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University.

Contact Us for Help

View staff by program area to ask for additional assistance.